About

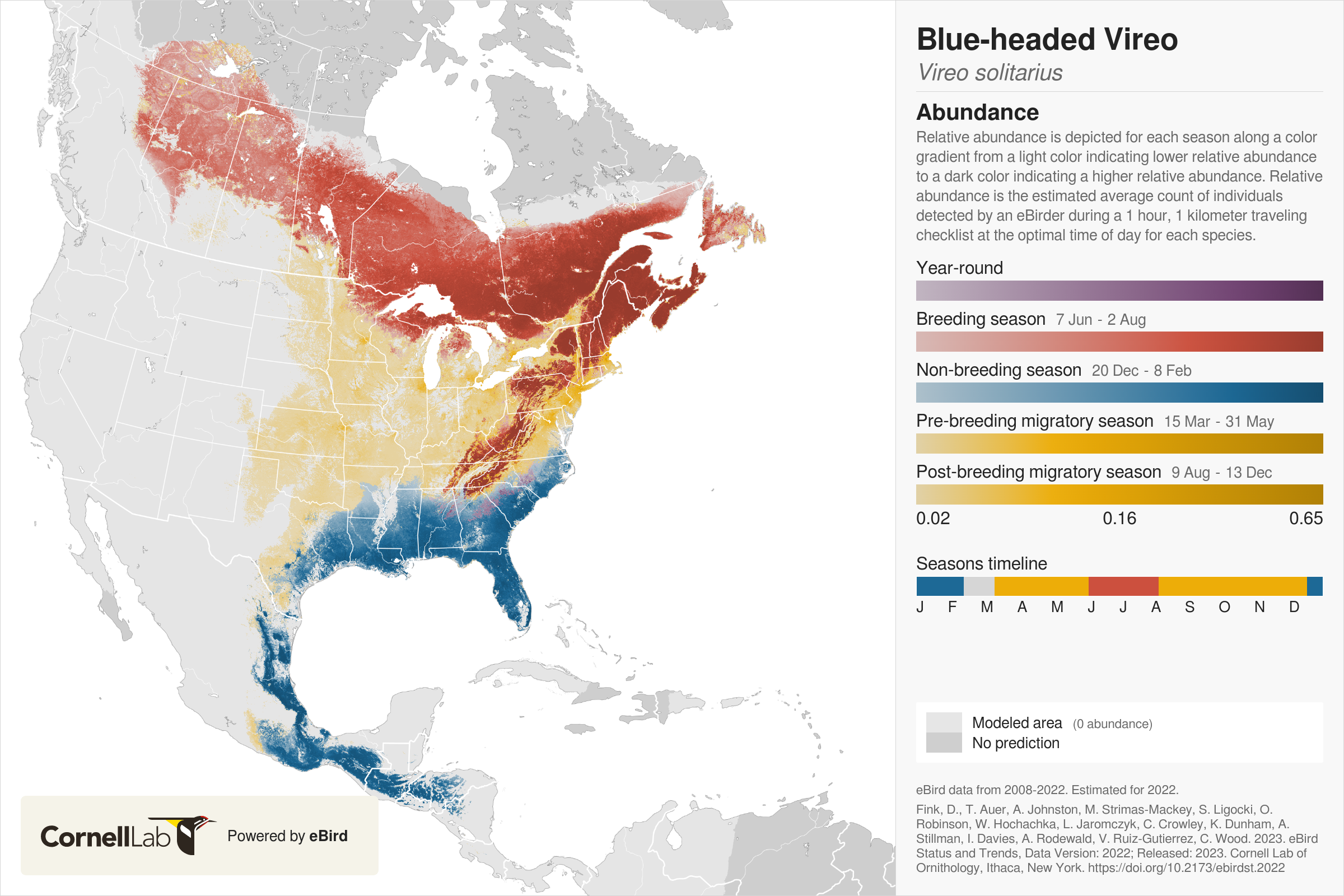

Why do data science? My only excuse is that I stumbled into it accidentally. Several years ago I was taking an introductory course in GIS applications (I like maps), and my final project was to select an example map and create a walkthrough to recreate it. I chose the abundance maps developed by eBird (I also like birds).

It turns out, these maps are generated with R, a statistical computing language, and not a GIS, so I redirected. But I had now discovered data science.

Data science is fucking hard. You have to learn programming. Then you have to learn statistics. Then you have to learn about bias. Then you have to learn best practices to avoid bias. Then you have to embark on an inward journey of the soul to investigate the source of your own implicit biases, identifying and eradicating fundamental parts of your established self-concept, and after several years of this and some complementary therapy, some janky fucking histogram is the best you can produce. Then you have to learn web design so you can publish your janky histogram.

Werner Herzog

Facts do not illuminate us.

But in the process of all of this I’ve developed a real appreciation for the folks who manipulate and use data to communicate on a daily basis, and its contribution to how we understand ourselves and the world in which we live. Werner Herzog has an interesting perspective on facts. He says, “Facts do not illuminate us.”

A data point is a fact, and a data set illustrates a trend, but it is up to us to translate the “facts” into a “story,” and stories transcend facts. A story is data arranged into Meaning. The scientific method prescribes that we approach the world with ambiguity, and this is largely useful. But it does not inspire us to incorporate new knowledge into our lives joyfully and creatively. Data can help tell a story, and the story invites us to consider how facts might contribute to new possibilities.

I adhere to the principle that publicly practiced science has greater epistemic authority. That said, I am not a formally trained data scientist, or any other kind of scientist. My interest in this field stems from a commitment to the craft of landscape design. To me, craft is the synthesis of art and science. Art informs creative freedom, science informs the limitations within which art is expressed. Much of what is popularly believed about landscapes is not scientifically derived. Ecosystems do not respond obediently methods of control. It is ultimately my hope to use data to illustrate the complexity informing the aesthetic appeal of wild beauty. This is the scientific component. It informs the limitations from which the artistic component emerges.